That Unbearable Plane Ride Home

Memoir Essay

March 17th was the 23rd anniversary of my brother’s death. I know he’d enjoy the fact that I’m still talking about him. He loved attention. So, I am resharing this post that I wrote a few years ago. Hug ‘em while you got ‘em.

First published in P.S. I Love You on Medium

“I hope I die before mom does. I couldn’t handle it, no way. I want to go first.” — My Big Bro, Miram/Jack

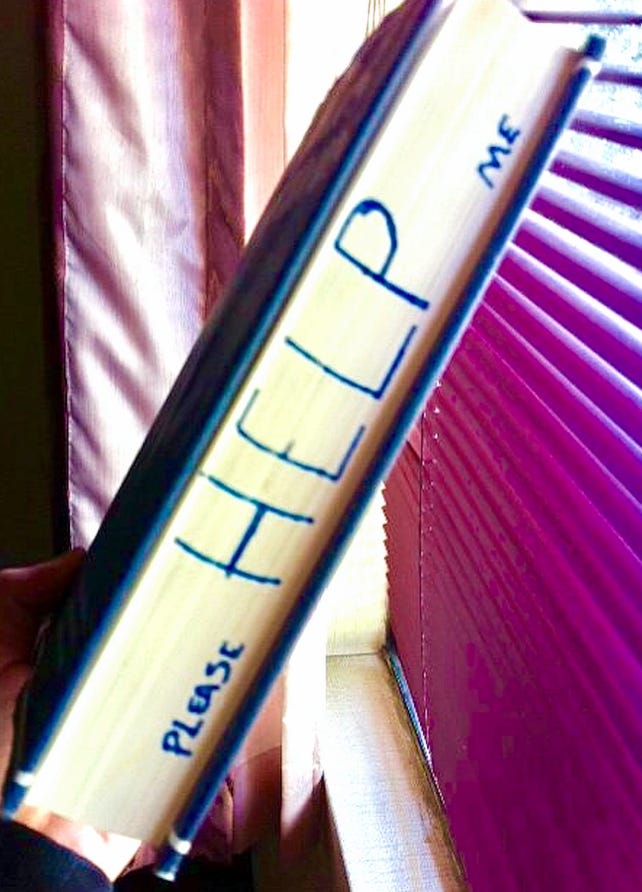

It’s an all-encompassing desire to wish to save another. I know. I tried for most of my childhood. I held this desire in my tiny ten-year-old hands when I thought I could write my older drug-addicted brother a heartfelt letter to convince him to quit doing drugs.

This letter would be so powerful that it would snap him into sobriety!

My well-thought-out words would ignite a flame inside of my big brother’s heart that would warm him up with so much sibling love that the mere thought of doing cocaine again would never enter his mind.

Upon reading my letter, my brother would be healed. Upon reading my letter, his pains would be soothed. Upon reading my letter, I would get my brother back.

He’s a charmer.

His mischievous grin opened doors. He could convince anyone of anything. He was an exceptional liar. But mostly, I remember how sensitive he was. When I was around ten years old, he was about 20; he came into my room one night crying. He knelt down beside my bed, and he shook me awake.

“Annie, wake up, wake up, I need to talk to you!”

I woke up to see my big brother balling his eyes out. I asked him what happened. He told me that his girlfriend, Carol, had left him. She doesn’t love me anymore. What should I do? What should I do? I’m ten years old. How the heck should I know? But I didn’t say that. I just hugged him and patted his head and told him the thing I heard grown-ups say, “Don’t cry, everything is going to be okay.”

But… spoiler alert! It wouldn’t.

He loved the letter.

He was so moved by his little sister’s letter that he had it framed and hung it up on the wall of his beautiful, new apartment. He couldn’t wait to show me. I. was. livid.

The conversation went something like this:

That’s private! I screamed.

But it’s so good. And sweet. Everybody loves it, he replied.

It’s not for everybody! Did you even read it?

Of course.

And?

And, I told you… It’s so good. And sweet.

I made him take the letter down.

When I got older, my brother would take me to all the trendy clubs.

Everybody knew him — we’d always just walk right in — the bouncers usually gave him a big hug hello. Hey, Jack! That was the American name he chose for himself. He’d always introduce me as his little seeester. This is my little seeeester, isn’t she cute? He was so proud of everything I was and everything I did. I wanted to be proud of him, too. Why did he make it so difficult? Back then, I didn’t know addiction was a disease; I thought it was a choice. But why would anyone choose such a thing? They wouldn’t.

“What is an addiction, really? It is a sign, a signal, a symptom of distress. It is a language that tells us about a must be understood.” – Alice Miller, Breaking Down the Wall of Silence: The Liberating Experience of Facing Painful Truth

During my teens and 20s, every late-night phone call sent chills up my spine. I always seemed to be worrying about my mom’s physical health and my brother’s mental health. Worrying is exhausting.

There was a time when my brother seemed happy. He was successful and had fancy cars and fancy friends, even some famous ones that he’d often convince to call me on speakerphone to impress me. Jack loved his phone and his pager.

You can actually catch a glimpse of my brother on the phone, in a popular pager store at the time, in the 1996 documentary Heidi Fleiss: Hollywood Madam. I had no idea he was in the documentary until I watched it years later. What was his involvement with the Hollywood Madam? Yeah, I have no idea. Like most of my brother's life, I have more questions than answers.

Our parents felt so overwhelmed, so I, the baby of the family, was the one at age seventeen who drove Jack to his first meeting. I think he only went to AA meetings when it was mandated by the law from one of the situations our dad bailed him out of.

I found a psychiatrist for him, and after I picked him up after the first session, he bragged, She thinks I’m great. Then he laughed to himself. Like I said, he could convince anyone of anything. Or was he lying? Or a little of both. But the thing is, he was great. And also, he wasn’t.

Addiction begins with the hope that something ‘out there’ can instantly fill up the emptiness inside. — Jean Kilbourne

I used to ask him why he took things so far. I mean, in the late 1980s, a lot of Hollywood was partying. But for some, partying was just that. A thing you did socially. A wild, good time. But for addicts…for addicts, it was a whole other ball game. I see that now. But, then, then… I just couldn’t comprehend.

When that late-night phone call finally did come, the decades of worry was shocked out of me like a sucker punch in the gut.

My brother was gone. He was 41.

My mom was in Las Vegas at the time, playing her much-loved quarter slot machines. To this day, I sometimes think about my mom on that plane ride home alone, having just found out that her child had died. Did a stranger comfort her? Did she cry? Pray? Was she stunned silent? It hurts to think about it, but I can’t help it.

What was it like, that unbearable plane ride home?

I get it now. I know that no matter how much we think we can change another person, that’s not how humans work. We don’t change them. They change them. Whatever journey my brother was on wasn’t mine. His thoughts were not mine. His pain was not my pain. His brain functioned in ways I couldn't possibly understand. We can never truly know what’s going on inside the hearts and minds of someone else no matter how much we love them. No matter how framable of a letter you write.

You can’t change other people.

(But maybe try anyway. Just in case.)

The father character in my book, Just a Girl in the Whirl, was inspired by my brother.

If you need help, call the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Adminstration (AMHSA) National Helpline — 1–800–662-HELP (4357)